Too Preoccupied to Care if You Fail

“You wouldn’t worry so much about what others think of you if you realized how seldom they do.” – Eleanor Roosevelt

“Shyness has a strange element of narcissism, a belief that how we look, how we perform, is truly important to other people.” – Andre Dubus

We’re often too preoccupied either worrying about how we are perceived by others or overly focused on ourselves to notice what people are doing around us. We wrongly believe that we are the center of attention in different settings, causing undue stress about how we may appear to others. This false belief and anxiety then freezes our decision-making and restricts our choices, which diminishes the satisfaction that we would otherwise have if we acted differently.

Thinking People Notice You

“Most of us stand out in our own minds. Whether in the midst of a personal triumph or an embarrassing mishap, we are usually quite focused on what is happening to us, its significance to our lives, and how it appears to others. Each of us is the center of our own universe.” (Source)

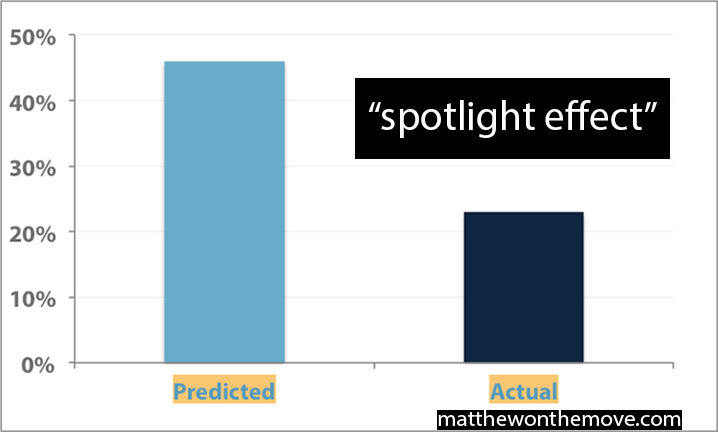

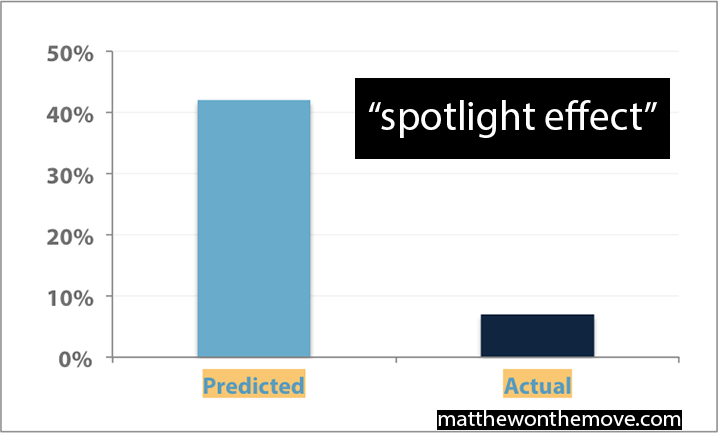

Humans as a whole have been shown to have this self-centered mindset. The degree varies with age and mental development, with younger children remaining egocentric and unable to understand alternative perspectives. In adults, the selfish occurrence was demonstrated by Thomas Gilovich, Victoria Medvec, and Kenneth Savitsky in a set of experiments in the late 1990s, as participants were asked to wear embarrassing t-shirts of a singer (Barry Manilow) in a room of others and estimate how many of the people would notice their t-shirt. The predictions in the 1st embarrassing trial were in fact twice as high compared to what those in the room reported observing. In a 2nd non-embarrassing trial, students this time donned a t-shirt of a celebrity of their choice, and again predicted how much others would notice the t-shirt element (see trial results below). The 2nd trial participants “substantially overestimated how attentive the observers were to this element of their appearance” – the average estimate of who would notice was six times higher than the group’s actual observations of the t-shirts. This is precisely what has been termed the “spotlight effect:” “People overestimate the extent to which others are attentive to the details of their actions and appearance. People seem to believe that the social spotlight shines more brightly on them than it truly does.”

Spotlight Effect: Overestimating Attention Directed At Us

Predicted vs. actual observations of who notices you (Trial 1)

Predicted vs. actual observations of who notices you (Trial 2)

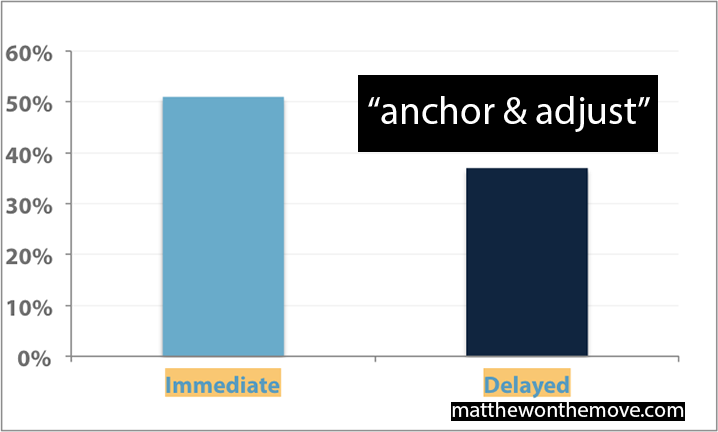

In a later experiment, participants were asked to wear the embarrassing shirt and either go into the room immediately or to do so after a 15 minute delay. Those in the condition that waited 15 minutes were allowed to hear others and become accustomed to wearing the shirt before entering the room. This delayed group ended up predicting that their shirt would be less noticed against the sample that went immediately into the room (refer to below). As the authors note, “Because participants in the delay condition were allowed to habituate to the T-shirt, it was a less intense focus of their own experience.”

Anchor and Adjust: Assess Perception

Time and habituation reduces the spotlight effect

Source: The Spotlight Effect in Social Judgment: An Egocentric Bias in Estimates of the Salience of One’s Own Actions and Appearance

Source: The Spotlight Effect in Social Judgment: An Egocentric Bias in Estimates of the Salience of One’s Own Actions and Appearance

Once we have time to acclimate to something new, we may also realize that it’s less noticeable even to ourselves, which we then indirectly assume will be the case for others. We project our own depiction of reality unto those around us. This new person, place, item, or employment becomes the new baseline in our consciousness, like a new haircut after a few days. Developing this tangent further, the three authors of the spotlight effect studies suggest that “repeated exposure and habituation can dampen the spotlight effect, and perhaps sometimes even reverse it.”

The spotlight effect is a survival mechanism as we have to care most about ourselves to safely navigate around everyday dangers and ensure our survival. But on the other hand, as we place ourselves at center stage, we overemphasize how much others notice us. This leads us to exaggerate the social repercussions and awareness of making a mistake, limiting the opportunity set of our choices and personal growth. We end up fearing to take action because we are “concern(ed) with how failure would look like to others.”

This inaction, derived from the spotlight effect, poses a very material risk to the satisfaction that we experience during our time on Earth.

Here’s the thing: “No one really cares that much about what you’re doing. People are highly self-absorbed.” Many people are self-interested and self-serving (I am just as guilty as anyone else). I say this not to discourage, but rather to counteract an overly rosy view that everyone cares — a sort of healthy pensive optimism. It’s an attempt to shift beyond the make-believe of the daydream into a process of “mental contrasting” where a wish, outcome, obstacle, and plan framework is established to help ground fantasy in reality to move through inaction. Past our fear of our appearance to others and the spotlight effect.

People Are Mostly Concerned with Themselves

This obsession of our appearance and self has only been on the rise over the past several decades within the context of the “self-esteem movement.” Scores on self-assessment against others on a range of aptitudes in academic ability, drive to achieve, or mathematics have continually gone up, as measured in American students. This is known as the “above average effect,” described as an illusion of superiority over our peers.

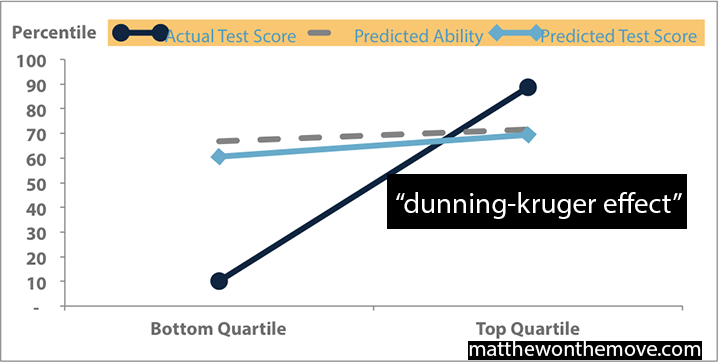

This illusion has been demonstrated in landmark research by Justin Kruger and David Dunning in 1999 to be more common in incompetent and unskilled people. Participants were asked to rate how well they would do and then had their real scores compared in humor (emotional intelligence), logical reasoning, and English grammar tests. The results are striking. The worst performing (bottom quartile) participants not only grossly overestimated their self-ranked ability relative to peers and their test score results, but performed miserably. Like really bad (the graph below is from the English grammar study). While the incompetent greatly overestimated their abilities, the competent tended to underrate themselves. This overly optimistic view and miscalibration people have of themselves is named after the authors as the “Dunning-Kruger effect.” The authors consider that incompetent individuals view themselves so highly because they “seldom receive negative feedback about their skills and abilities from others in everyday life.”

Dunning-Kruger Effect

Ignorance is Bliss

This negative agnostic, positive reinforcement is a hallmark of the self-esteem movement in classrooms. But in fact, it has been determined from over 200 research papers that too much praise to students could make students less likely to succeed as it risks to “convey a message of low expectations.” What the self-esteem movement has done is contribute to more arrogance and self-centeredness, despite no change or even a slump in real abilities. Telling students how awesome they are certainly makes them feel wonderful, even if their abilities are lackluster. But feeling and doing are not one in the same.

The number of hours that American university undergraduates study has dropped from 24 hours/week to around 15 hours/week today. In the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), mid-teenage American scores in math are sliding, while reading and math results stagnate since a decade. Meanwhile, university students spend 8-10 hours a day on their cell phones, becoming increasingly addicted to their smartphones. The problem is particularly acute in Korea (where I live), with more than 1 in 5 students identified as addicted by the government. (Anybody who knows me can vouch that I am also constantly connected to my smartphone, although I am mindful and trying to change my behavior.) All of this is happening as grade point averages for students continue to climb in what’s termed “grade inflation” while over one-third of students fail to make any meaningful gains in critical thinking skills after spending four years in college.

Grade Inflation

A Rising Tide For All

Source: Ivy League Grade Inflation: Grade Expectations (The Economist Magazine)

Depressingly, Millenials (the generation born post 1981) are more drawn to extrinsic goals of wealth & status versus intrinsic goals, less concerned about others, and less civically engaged (especially on the environment) compared to Baby Boomers (born 1946-1961) and GenX’ers (born 1962-1981) concluded a study in 2009.

This population segment has been termed “Generation Me,” giving rise to the mentality I amusingly describe as “Me, me, me…now, now, now!” The rapid adoption of smartphones and social media has opened up the floodgates of what I call “narcissism on steroids.” This is reflected in a significant increase of narcissistic traits in American university students on the Narcissistic Personality Inventory questionnaire since the early 1980s (I apparently rank high in the vanity arena – it’s worth a try).

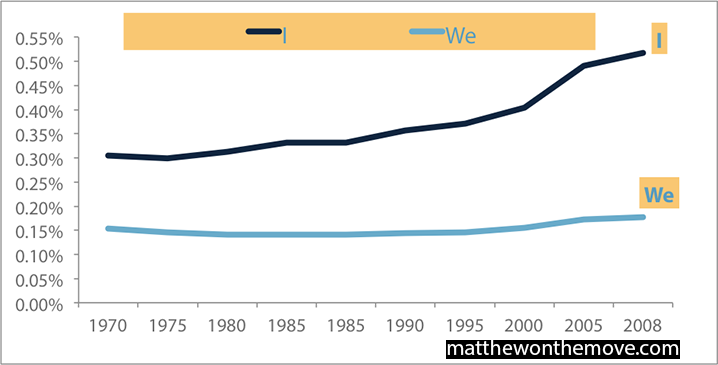

And this self-centric behavior is reflected in literature and music. There has been an observable upward trend in the use of personal pronouns (I, me) against inclusive pronouns (we, us) in books since the 1960s as can be seen in the Google books Ngram Viewer-generated graph underneath. The togetherness theme of the 1970s and 1980s has been replaced by an increasingly individualistic style of music. As researchers concluded in a metadata analysis, “Changes in popular music lyrics mirror increases in narcissism over the past 27 years, with musical lyrics becoming increasingly self-focused over time.” Inward-looking behavior has been encouraged through technology and promoted in popular culture.

The Rise of Personal Pronouns in Books

Narcissism on steroids: it’s all about me

Source: Google Ngram Viewer (via www.matthewonthemove.com)

Your Friends Are More Popular

“People have fewer ‘friends than their friends have, but they believe they have more friends than their friends.”

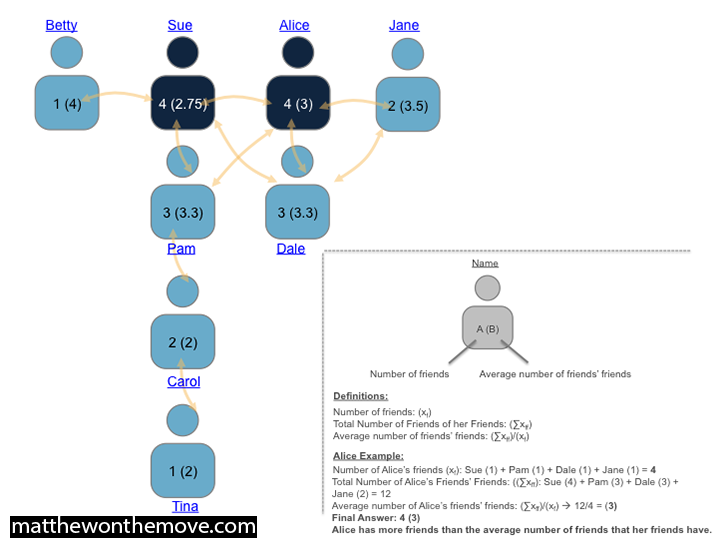

The context behind this sentence comes from the psychologist Scott Field. In 1991, he observed the structure and makeup of real-life social networks (studying class sizes) and determined that most people on average have fewer friends than their friends have. Simply stated: Your friends are more popular than you are.

How can this be?

Essentially, a few well-connected “hubs” have numerous friends, and those hubs with their large friendship base end up skewing the average for the rest of the network. As we can see below in a sample social network used in Field’s examination, all of the lightly blue colored people are less popular than their friends (meaning their number of friends < average number of friends’ friends)…except for the minority hubs of Sue and Alice in dark blue. Sue and Alice have noticeably more friends than the rest of the network. This pushes up the average number of friends’ friends for Betty, Pam, Dale, and Jane. “So most people have a few friends while a small number of people have lots of friends.” (Source)

Interestingly, but not surprisingly (think back to the spotlight, above-average, and Dunning-Kruger effects), we are insensitive to this reality. Our self-serving cognitive bias and personal motivation lead us to believe that still we have more friends than others. Reality and fiction are at times up to the interpretation of the individual.

Friendship Paradox: Your friends have more connections

The rolodex extends far for some

Source: Why Your Friends Have More Friends Than You Do

Wave of Noise and Information Overload

This friendship paradox carries over into social media. Researchers peered through the “Firehose” (full data-stream) of all tweets on Twitter among 5.8 million users analyzed in 2013 (for some 193.9 million links between them). Analysis was also done on Facebook, to sift through 721 million users in May of 2011.

On Twitter, amongst the 5.8 million users analyzed, it was discovered that “both friends and followers are more popular than the user” –– 99% of those followed (friends) have more followers and 98% of followers had more followers than the average user. Both the people you follow and your followers get more traction.

Not only that, but the friends and followers were overwhelmingly more active in posting tweets. Who you follow and your followers are tweeting more.

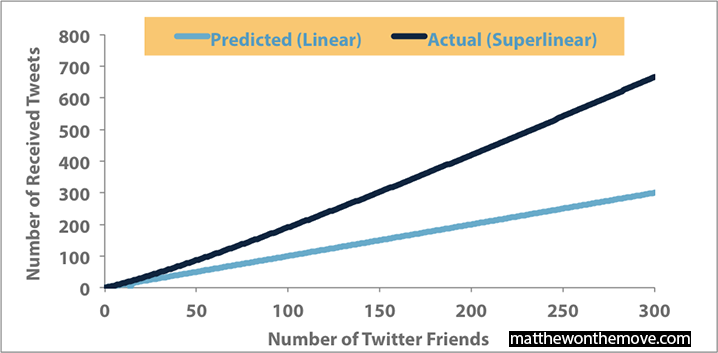

This means that as someone becomes more active on Twitter and follows more people, “the volume of new information in a user’s stream will grow super-linearly as new connections are added.” In fact, we quickly may reach a state of being overwhelmed and saturated as we are bombarded by a chorus of new notifications, “pushing the user into information overload regime.”

Friendship Paradox on Social Media

More friends, more problems

Source: Friendship Paradox Redux: Your Friends Are More Interesting Than You

In the case of Facebook, the median number of friends amongst 721 million global users analyzed is 99. Referring to the friendship paradox (your friends have more friends than you), a user with 100 friends was discovered to actually have 40,300 non-unique friends-of-friends, orders of magnitude greater than the predicted 9,900 friends-of friends if each of those 100 friends were to have the 99 median friends. But that’s not the case, the friendship paradox is at work and some very popular hubs move the friends-of-friends’ needle for everyone else. The interconnected digital age of today accelerates and magnifies real-life social networks and underscores the importance of interpersonal relationships as I have written.

Learning from the Regrets of the Experienced

“Inaction breeds doubt and fear. Action breeds confidence and courage. If you want to conquer fear, do not sit home and think about it. Go out and get busy.” – Dale Carnegie

Earlier we saw how we are paralyzed by fear of how we appear to others from the spotlight effect. This paralysis weighs on our decisions, at times pushing us to stay put with the status quo. To get a better understanding of the gravity that inaction can have on our well-being, it’s worth considering the five documented regrets of the dying. Those in the their deathbed looking back on their lives:

- I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.

- I wish I hadn’t worked so hard.

- I wish I’d had the courage to express my feelings.

- I wish I had stayed in touch with my friends.

- I wish that I had let myself be happier.

We can observe that four of the five regrets of the dying relate to not having done something.

As eloquently and concisely stated from these regrets: “Don’t ignore your dreams; don’t work too much; say what you think; cultivate friendships; be happy.” – Paul Graham

“Living a life with no mistakes and without any regrets is extraordinarily difficult to accomplish. A lifetime of making choices brings with it the knowledge at least some of our actions were ill-considered, some failures to act unwise. For most of us, it also brings with it the realization that some of these unfortunate outcomes could have been avoided. To live, it seems, is to accumulate at least some regrets.” (Source)

So we all have regrets, and it seems that as life goes on we collect them. But how does regret work – is it from making a mistake (commission) or from a missed opportunity (omission)? Well, it turns out that while we do regret our commissions — those mistakes and blunders — in the short-term, it’s those times we failed to act — the omissions — that haunt us over the long-term. “Actions produce greater regret in the short term; inactions generate more regret in the long run.”

Just as we see with the recently documented regrets of the dying, psychologists Thomas Gilovich and Victoria Medvec (the same who ran the Spotlight Effect t-shirt studies) commented in their 1995 study on regret:

“When people look back on their lives, it is the things they have not done that generate the greatest regret.”

There are several physical and mental factors that reduces our regret from action and magnifies our regret from inaction. Here’s an overview (quotes are from the 1995 study):

Reducing the pain of regrettable actions:

- The first way we reduce ill feelings from regrettable actions is by taking compensatory action to improve regrettable actions. “The do something principle” states that it’s easier to build momentum by breaking away from a static resting state with action than by doing nothing. “Whenever people act, they overcome whatever inertia had kept them in the position they were in beforehand.” On the other hand, being comfortable to hesitate in doing nothing and then trying to gather some movement doesn’t work as well since the initial inertia serves as a barrier. “Whatever it was that made it difficult to pull free of these forces initially [of inaction] often makes it difficult to pull free later on. It is relatively difficult to change from initial inaction to subsequent action.”

- Secondly, when we do something and get it wrong, we often think of the silver lining in the dark cloud of the regrettable event: “well even though it wasn’t the right decision, at least I learned from it…”. Indeed, “People typically learn more by doing new things than by sticking to old patterns.”

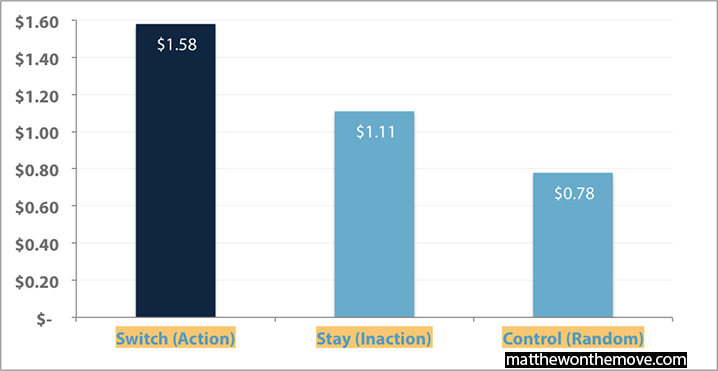

- The last method in mitigating regret from action is by employing more cognitive dissonance reduction for our actions versus inaction. “Thus, because people’s regrets of action are more salient, more painful initially, and engender more of a sense of responsibility, they should elicit more cognitive dissonance.” An experiment was conducted where people were provided a choice, with some sticking with their original choice (omission) and others switching (commission). No matter the condition, each group ended up with a modest prize and were then shown a grand prize; it turns out that those who took action demanded a higher price to sell back their prize than those who had done nothing (see below). Taking control of one’s circumstances enables a feeling of mastery, and is in turn more relevant in one’s mind — requiring more effort to surpress any aroused regret. This repression weakens our feeling of regret over the longer-term.

Regret: Valuing Action over Inaction

Pay me more for what I decided to do

Source: The Experience of Regret: What, When, and Why

Increasing the pain of regrettable inactions:

- The first way that we increase the pain of regrettable inaction is from inflated confidence with time: the concerns we had in inaction become less memorable to us as time goes by. “The further removed we are from the occasion, the more convinced we become that we could have or would have done just fine.” Our confidence increases with time that we could have done something in the regrettable inaction scenario. We wonder to ourselves “why didn’t I just act?” in the years following the event.

- A second method is about activities defined as either a compelling or restraining force. Compelling forces are easier to recall than restraining forces, “that which compels has a greater impact than that which impedes.” We place a premium on adding to enhancing results (compelling force) compared to subtracting to detract from results (restraining force). Students believe studying a certain amount of time will help them answer more questions correctly overall than the total negative effects of missed answers due to not studying.

- Lastly, the effects of our action are confined and finite, while the missed possibilities and potential from inaction are limitless and infinite in our minds. Boundless. Our imagination catches up to us and torments with the nagging question “what if I had done that?”

A last psychological phenomenon is called the Zeigarnik Effect: “People typically are more preoccupied by and perseverate longer over incomplete tasks than completed ones “ Things that aren’t yet finished stick longer and pop up more frequently in our mind than completed tasks. Whereas our action may spark our senses in the short-term, our inaction lingers long after the event.

Trying & Failing in a World of Selfies and Status Updates

What I’ve learned is to not be afraid to embarrass yourself! As the authors of the spotlight effect wrote: ““repeated exposure and habituation can dampen the spotlight effect, and perhaps sometimes even reverse it.” You may eventually find through experiences that much of your fears were misplaced and constructs of your “center of the universe” condition.

I’ve come nearly to tears when confronting past colleagues about my decision to resign from the firm I had been working (read: struggling) for many months before making the final decision to leave. I replayed an imagined and fabricated scene in my mind repeatedly that never came to fruition. A succession plan was rapidly established with a handover to the new hire. I said my goodbyes and moved on, as did everyone else (admittedly without much effort for them). And since then, I’ve witnessed over a dozen colleagues leave within months after being hired in a new firm, while also seeing numerous friends leave their jobs and move countries altogether. While all of this is certainly emotionally & physically draining and exhausting, people carry on with their day. Some may even continue as if nothing had happened for the most part (something I find difficult to accept and digest). Life goes on. People inherently have to adapt to survive, with their inward-looking spotlight effect.

As we have seen, most people don’t really notice what you’re doing in the first place, although they likely believe you notice them through their spotlight effect bias. They tend rather to be more concerned with themselves as is reinforced and rewarded in varying forms of media and lifestyle habits, which give rise to a narcissistic “Generation Me” on the back of the self-esteem movement lacking negative feedback mechanisms, in conjunction with smartphone addiction and an increasingly egocentric pop culture. All the while, we have examined through the friendship paradox that others have more friends on average than you do. They can become easily distracted and overwhelmed by a flood of noise from having all these additional friends with the information overload that accompanies the digital age. We finally observed that in the long-term, we regret more our inactions (omissions) than our actions (commissions).

So it logically follows that we should then endeavor to do all that we can to act upon our wishes. We won’t be as noticed as we think and we’ll regret that choice less in the future.

Get used to being bold and mustering the courage to take a measured risk in life. People around you won’t notice, won’t remember, or likely won’t even give a damn about what you are doing anyhow. Most people are too worried thinking about themselves or how they will be perceived by others to notice what you will do in the first place. We’re all pre-disposed to fall into the delusion of the spotlight effect – it’s a trait innate in humans. Recognizing this bias is in fact incredibly liberating as it allows you to try and do many things that largely go unnoticed! Rather than languishing in the despair that nobody cares and are only concerned about themselves, capitalize on the indifference of others to make your decisions and craft life on your terms.

Sing the song, call the girl, talk to your boss. Dare. Dream. Learn. Act. Buy the ticket. Take the risk. Go. Do!

This will ultimately lead to a more meaningful and fulfilling life with less regrets caused by inaction.

Now back to being distracted and preoccupied with myself.